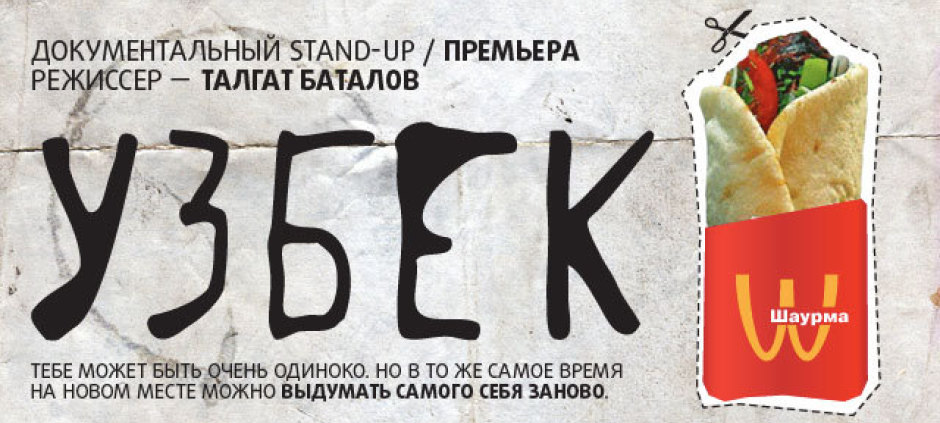

Uzbek

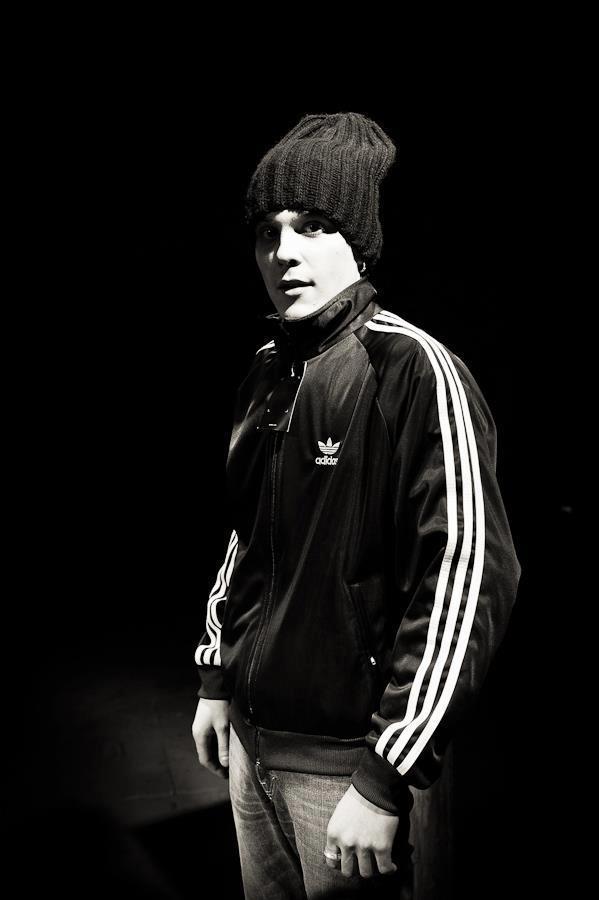

JOSEPH BEUYS THEATRE, TEATR.DOC AND ANDREI SAKHAROV CENTRE, MOSCOW Written, directed and performed by Talgat Batalov Produced by Georg Genoux A first-hand documentary solo performance by a young author about the cunning and senseless bureaucratic mechanism of immigration agencies in Russia. Talgat Batalov was born in Tashkent, and though his blood is a mixture of Russian, Tatar and who knows what else, in his passport, he is registered as "Uzbek". With this passport, he had to go to hell and back in order to obtain Russian citizenship and avoid being drafted into the Russian army. How did he do this? he had to leave his parents’ apartment and automatically cease to be a citizen of Uzbekistan, register in a remote village near Tver, get access to the local passport office for a bribe and renew his registration regularly. Moving around the audience, seated in a close square on the stage, Batalov gives them his real documents to hold, and we’re shocked by what is written on them. But he can’t go anywhere without those papers, so the author asks the audience to return his battered documents to him after the show. From the subject of papers, the performance turns to the subject of national identity, which the false "Uzbek" Batalov has problems with. Human rights activists, who he asked for an explanation, turn out to be demagogues, while real Uzbeks are beaten and abused on the streets of Moscow. And the final shots of an old black and white film about friendship among Soviet peoples reflects only nostalgia, not the truth. Kristina Matvienko I am now standing in front of you performing the play only thanks to the fact that once my Russian grandfather and my great-grandmother, who fled from Kharkov during the war and travelled across the country were received and fed by Uzbeks. An Uzbek family gave them shelter, and they survived. And it means that in a certain sense, I am alive, thanks to Uzbeks. It is a very simple, even a sentimental statement, but it is really so. Talgat Batalov, interview to Bolshoi Gorod Batalov wrote a play about himself – an actor and director from Tashkent, who at home worked at the famous Ilkhom Theater led by Mark Weil. In Uzbekistan, he was regarded as a Russian, while in Russia he is considered to be Uzbek. His performance is a documentary stand-up, a unique experience for our theater of an actor telling a story about his own fate, making his monologue in the first person, and speaking to the audience without external effects. A green Uzbek passport with a long-forgotten "nationality" section, an Uzbek registration certificate, a declaration of renouncing the citizenship of Uzbekistan - all these documents are sent along the rows, for the audience to feel to the touch the personal biography of the performance author. Talgat, whom one feels like calling by his first name, the more so as he is the only hero of the performance, lets us touch his innermost, exposing what is actually seldom shown even to closest friends. There is a desire to share something very important in it, and also a feeling of insecurity and a need to open up to another person. THE UZBEK is more like a documentary transferred to the space of a theater, or a journalistic article with elements of an essay adapted for the stage, but not a theatre performance. Gazeta.ru The Uzbek has been nominated for the Golden Mask Award in Moscow as best experimental theatre project of the year (2013).and was included in the Russian Case program in Moscow and the Golden Mask Festival program in Warsaw (2010). The Uzbek also performed at the High Fest International Performing Arts Festival in Jerewan (2013. 'Uzbek' Shows Moscow Through Immigrants' Eyes By John Freedman June 21th 2012 Moscow Times Early in Talgat Batalov's self-directed, self-acted production of "Uzbek," the performer begins handing out passports and military service records for the audience to look at. "Don't forget to give those back to me," he says with a small laugh. "I still need them." "Uzbek" is more than theater or less than it, depending on your point of view. Like many performances and events at Georg Genoux's Joseph Beuys Theater, it is definitely a foray into social commentary. In recent years, as political developments have grown increasingly complicated in Central Asia, Moscow has become a destination of choice for displaced persons from Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Like many immigrants from Africa or Eastern Europe to Western Europe, or Mexico and the Philippines to the United States, these refugees have sometimes found themselves in a serious bind. They are underappreciated — to put it lightly — by the local population. They are easy targets for corrupt policemen and city officials. They generally wind up doing the dirtiest and lowliest work that any city can throw at a population. Batalov is the perfect individual to tell the story of at least a few of these immigrants since he is one himself. He was a member of the company of Mark Weil's Ilkhom Theater in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, when that world-renowned director was murdered outside his apartment in 2007. That was sign enough for Batalov that he no longer wanted to hang around and see how events would develop in Tashkent. He headed for Moscow almost immediately. Working with playwright Yekaterina Bondarenko, Batalov in "Uzbek" mixes the stories of several immigrants in Moscow with his own. But his own story shows how mixed up these things can be. "In Uzbekistan I was considered a Russian," he tells the audience. "But here I am an Uzbek." The irony thickens when he explains that there are 160 different nationalities living in Tashkent and, actually, by nationality, he is a Tatar. His family ended up in Uzbekistan because of mass evacuations that took place during World War II. Batalov seats the spectators in a circle in the middle of the hall at the Joseph Beuys Theater and walks around them, stopping in various places from time to time to add new details and introduce new characters into his narrative. "I'll tell you this," he says after handing his military service booklet to a spectator in the first row, "You feel just as bad in a Russian draft board office as you do in Uzbekistan." The actor's delivery is folksy and low key. He tells the first-person tale of an Uzbek immigrant who works in an open-air market. He reads a handwritten letter that his father once sent him, and relates some advice that his mother once gave him over Skype. He steps into the midst of the spectators and delivers a speech by then-Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin on Russia's tradition of being a multinational state since the 18th century. This is followed by a vignette of Batalov finally receiving his Russian citizenship. "Why are your hands so sweaty?" the woman handing him his documents squeamishly asked. "It's not every day I receive Russian citizenship," was Batalov's loaded, deadpan answer. Batalov doesn't take sides in "Uzbek." Almost everything he utters cuts two ways. Consider this, for example: He says everyone in Uzbekistan thinks there are gun battles on Moscow's streets all day long "because everybody in Uzbekistan watches only Russian television. Uzbek television is completely unwatchable." Or consider this short exchange from an interview he did with a police sergeant in Moscow. "Of all the people I have apprehended," the policeman told him, "Tajiks, Kyrgyzes, Uzbeks and such, the biggest cowards are Uzbeks." It's probably true, Batalov confirms. Cowardice was "instilled in them by the Uzbek government." Talgat Batalov's "Uzbek" is a brief but poignant stroll through some of the dangers, paradoxes, humor and nonsense that a person in the 21st century encounters when he or she demonstrates the hubris it takes to abandon one culture and take on another. Whether this is theater or whether it is primarily social activism in theatrical guise, it is a testament to human resilience as well as to the hostilities that most governments foster in regards to the individual.

Ein Text! Sie können ihn mit Inhalt füllen, verschieben, kopieren oder löschen.