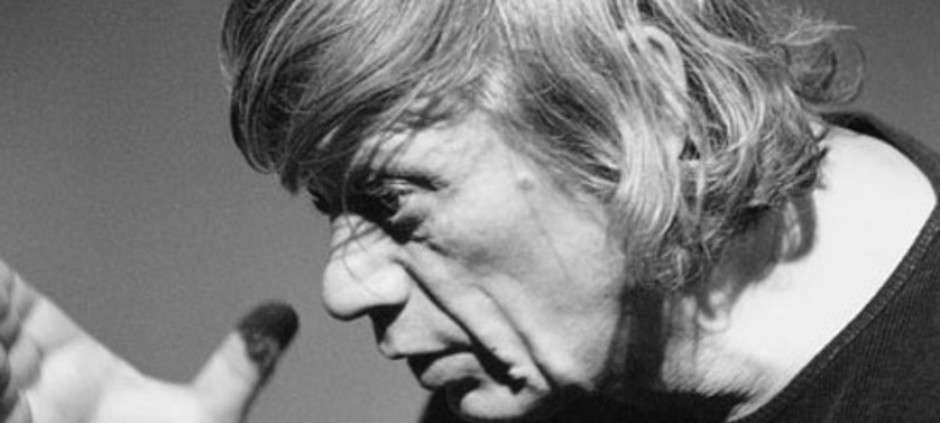

Face of a Foreigner

Documentary project about Dimiter Gotscheff by Kris Sharkov, Dessy Gavrilova, Irina Andreeva and Georg Genoux.

First work in progress presentation 28th of January 2014 at the Redhouse Center for Culture and Debate in Sofia.

The project premieres in May 2016

About Dimiter Gotscheff

Born on 26 April 1943 in Parvomei, Bulgaria, died on 20 Octobre 2013 in Berlin.

He accompanied his father to the GDR in 1962 where he studied Veterinary Medicine and Theatre Sciences at Humboldt University in East Berlin. 1968 pupil of Benno Besson, assistant director under Fritz Marquardt and contact with Heiner Müller, whose plays he has repeatedly performed since then.

From 1972 first productions in Bulgaria and the GDR, which he left in 1979 in connection with the expatriation of Wolf Biermann. Then productions in Bulgaria until 1985, including a famous production of “Philoctetes” in Sofia in 1983.

1985 invitation by the manager of the Kölner Schauspiel, Klaus Pierwoß, for a guest production of Heiner Müller’s “Quartet”. Gotscheff moved to Cologne and since then has worked only in German-language theatre. In 1991 he was awarded the prize of the Critics’ Association of the Berlin Academy of the Arts and was voted Director of the Year in the critics’ survey of the journal “Theater heute”. He received this honour for a second time in 2005 for his production of “Ivanov”.

1993 to 1996 permanent in-house director at the Düsseldorf Schauspielhaus. From 1995 to 2000 member of the management at Schauspielhaus Bochum during the management of Leander Haußmann. Since then, regular guest in Vienna, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt and Hamburg.

Portrait: Dimiter Gotscheff

Dimiter Gotscheff is a lonely phenomenon in German-speaking theatre. Although his age puts him in the generation of the famous manager-directors, such as Peymann, Stein, Zadek or Flimm, unlike these colleagues Gotscheff is still a welcome guest in all German-speaking threatres that have dedicated themselves to the contemporary. And he is by no means invited there for the modified classic designed to placate the subscription audience as compensation for too much modern material. Much rather, to this day Gotscheff himself is searching for this diffuse quality that is called avant-garde in the tradition of thought from which he comes.

The Bulgarian-born director, who found his way into the theatre and to Heiner Müller in East Berlin in the 1970s before he started his real directorial career in Sofia, has covered the entire dramatic cosmos since his move to Germany in 1986. From Sophocles to Dea Loher, from Shakespeare to Koltés he always develops his language from a clear duality: the empty space makes demands of the whole actor.

More than hardly any other current director, Gotscheff follows the philosophy of the poor theatre, which dispenses with the atmospheric first aid of great props. He wants to find the naked human soul, and for this thoroughly pathetic undertaking he seeks the qualities of a freelance theatre group within a municipal theatre. Since the early years, when Gotscheff mainly worked in Cologne and Düsseldorf, before he took over the unfortunate management of Bochum Theatre with Leander Haußmann and Jürgen Kruse in 1995, he has wanted the continuity of a travelling ensemble. Actors such as Samuel Fintzi or Almut Zilcher then moved with him to Hamburg or Berlin and are considered to be equaly sources of inspiration for his productions. The mutual support of this way of working was once expressed by the actor Dieter Prochnow: Gotscheff is the only director who really loves his actors.

But the artistic harmony that comes about from these family relationships is by no means tired of conflict. In good productions, such as his treatments of Heiner Müller or the brilliant new telling of Koltés’s “Black Battles with Dogs”, his second production of this material, which he launched at the Berlin Volksbühne in the 2003/04 season, tragic developments are acted bitingly and trenchantly. In unsuccessful productions his fragile actor theatre then has the effect of unfinished improvisations from the avant-garde museum.

Although with his constantly grim expression he looks like the epitome of a man who goes to the cellar to laugh and the mood of his productions tends to be gloomy, bare and pessimistic, his work does often contain fine humour and openness to cultural phenomena that is not automatically expected of sixty-year-olds. In his Koltés production at the Berlin Volksbühne, that uses irony to deal with stereotypes of black and white racism, Fintzi parodies the tribal rites of the Hip-Hop community. And in the melancholic Frankfurt production of Artaud’s “The Cencis”, he locks a crowd of naked people in a crypt as a choir of prisoners of advertising aesthetics. With this openness, Gotscheff suddenly came to command great respect among the younger generation of critics and theatregoers and, in his 60s, was finally invited several times to the Berliner Theatertreffen, something he had only achieved once before (1992).

Despite this recognition from a new generation schooled in pop culture, seriousness and concentration remain the dominant characteristics of his spartan theatre. Viewed in this way, Gotscheff’s productions are a contrast to the young environment in which he likes to work. With the reduction to the essence, the actor, he is very distinct from the wild-ironic poetry that is common in the theatre today. His view of the human condition strips it of all ornamentation to reveal an unvarnished truth. In our fashionable age, this approach is probably a sign of the true avant garde.

Till Briegleb